A Fake Artist Goes to New York

Social Engineering through Tiny Games. Waterstons Innovation: The Dots #19

Happy New Year! Here in the Innovation team at Waterstons have an exciting year ahead of us and we really hope you do too. We’ve got big plans this year. We’re going to open up our Innovation workshops to a much wider audience and we’re looking for a couple of new businesses to run it with. If you’d like us to run one for your organisation in return for a quote (hopefully on how amazing it is) then please get in touch. The feedback so far as been amazing.

I have found your training to be a breath of fresh air, challenging thoughts in a fun and energising way. The way you and your team bring a great energy is contagious and really helps lift the atmosphere of the typical drab training into fun and one I look forward to attending.

What is this? This is The Dots, our newsletter about exciting things we find in the world of innovation. We imagine innovation as connecting the dots; putting together a jigsaw. Our puzzle pieces are the pieces of interesting information we absorb in the world, our partners and their products. Innovation happens when we connect these pieces in new and interesting ways. This newsletter is about these dots we find and connect.

It’s no secret that I (Alex) love games. Board games, video games, puzzle games, all sorts of games. One of my favourite small party comes in a little bright pink box and is called A Fake Artist Goes to New York. Every time I’ve played it someone has been reduced to tears of laughter which is always the best sign of a good party game.

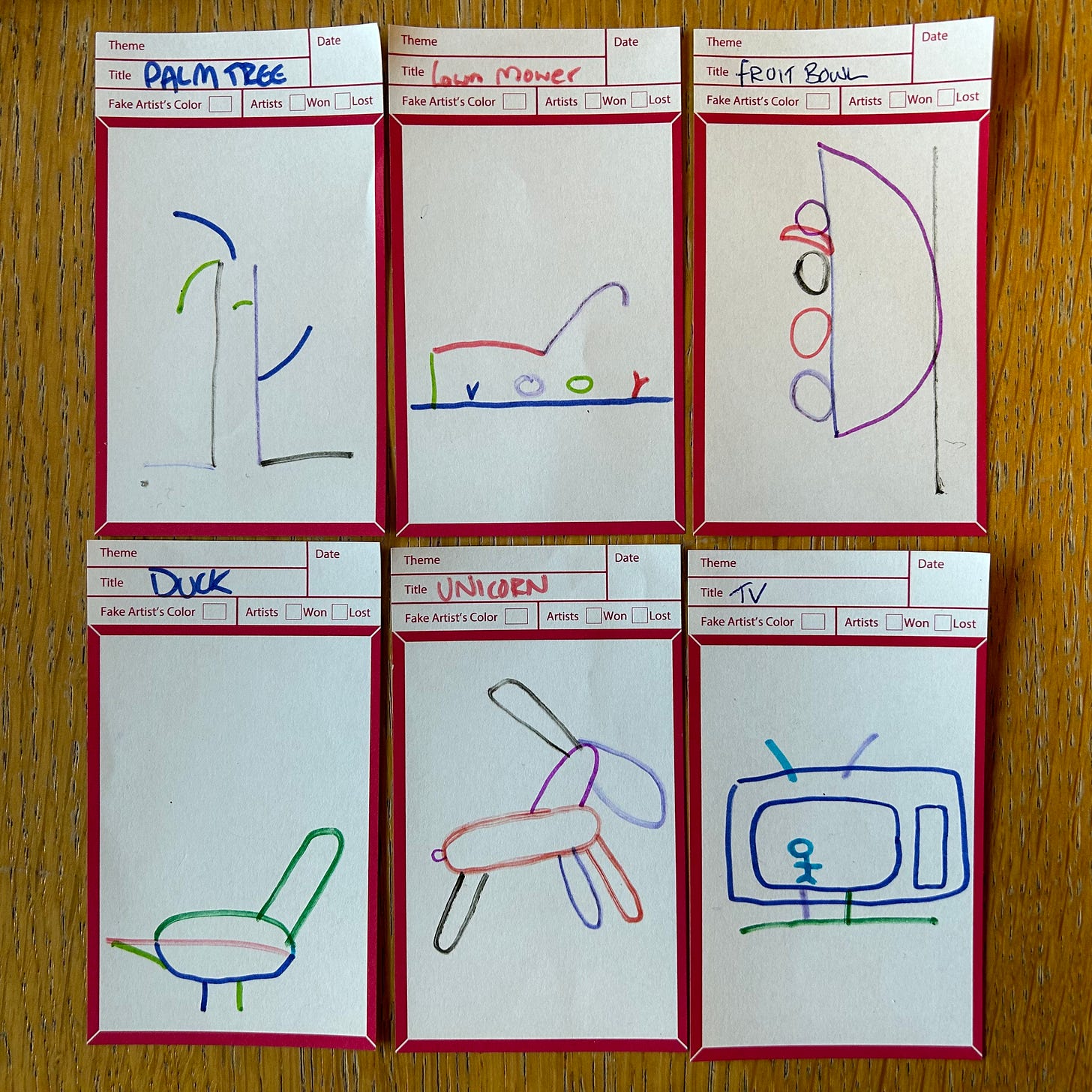

A Fake Artist Goes to New York is a deception game. Each round begins with one player, the Games Master, deciding what all the other players are going to draw. The other players then take turns drawing a single line on a communal sketch pad attempting to cooperatively produce a masterpiece. The big twist is that one artist is hiding the fact that they have no idea what everyone else is drawing. After everyone has drawn exactly two lines all the players vote on who they think the Fake Artist is. If they successfully sniff out the mole then the Fake Artist gets one last chance to guess what they were supposed to be drawing. If the Fake Artist remains undiscovered or manages to correctly guess what is being drawn then both the Fake Artist and the Games Master win. Otherwise all the other players win.

It’s a really simple game but it results in some extremely funny (and confusing) drawings. The real genius of it all though is in how much of the game is governed by unspoken social constructs created by the combination of the rules, the players’ motivations and the tension between the two teams.

I’ll use an example to explain what I mean. The first time anyone plays the game the first thing they ask is “What kind of line can I draw?” This is not explained anywhere in the (extremely short) rules. Is it a straight line? How long can it be? Can it be really long as long as the pen doesn’t leave the paper? None of these questions are answered anywhere in writing. Because they don’t need to be, the answer is very intuitive once you start playing. The truth is, though, that if you tried to write down a rule for this it would either make the game long and boring by constraining everyone too much and requiring constant measuring:

Draw a single straight line without lifting the pen from the paper. It can be no longer than 2 centimetres.

Or the rule itself would be long and boring and quite confusing:

Draw a line that is unambiguous enough that it makes it clear to the other Real Artists that you know what you’re drawing but that is ambiguous enough that the Fake Artist cannot tell what the subject actually is.

Without a specific concrete rule this desired woolly behaviour emerges naturally as a result of the context of the game. I think about the beauty of this every time I play. For a game that takes two minutes to explain its crisp rule set creates this deep level of social engineering. Product designers, policy makers and behavioural engineers the world over have been trying to do stuff like this unsuccessfully for years.

Here’s another example. It is possible for the Games Master to tell everyone to draw something extremely challenging but players in this position never do that. There are several factors at play that prevent them from doing so:

First, the game is not fun for anyone if someone does this.

Second, the Games Master only wins if the Fake Artist wins so they are motivated to choose something that is simple enough that the Fake Artist can quickly guess what it is and either blend in or answer correctly if they are sussed out.

Thirdly, the Games Master can choose who the Fake Artist is, really emphasising the social contract between the two team mates and putting pressure on them to work together.

The game is a masterpiece of design work and I strongly recommend you pick up a copy. I wanted to write about it in this innovation newsletter because of this elegance but also because of the way it rewards people who can both think differently and can communicate their ideas in the simplest possible way. As a player, drawing something that clearly resembles the topic is the simplest way to make it obvious to everyone else that you are a Real Artist but that also risks tipping off the Fake Artist. If instead you can think laterally and draw a line that reflects some obscure element of the topic instead of a main feature then you can both ingratiate yourselves with your fellow artists and totally bamboozle the Fake Artist at the same time. This can, however, backfire spectacularly - I was once in a game where we were all drawing an eye. One player decided to draw the eye from the side - a stroke of genius if everyone else had been in on it but it proved ultimately to be that player’s downfall when nobody realised what they were up to.

This is so much like innovation that it almost hurts. The corollaries are myriad: from not wanting to tip off your competitors to failing to get everyone else on board and ending up with something not only unrecognisable but often completely unusable. There’s also the fact that the best way to play as an imposter is to draw a bold feature with a confidence usually befitting the crisp-suited sales person for a new AI-driven recruitment platform.

I’m fascinated by how the mechanics seen in games can be applied to work. I was recently told to listen to Ezra Klein’s interview with C. Thi Nguyen and I strongly urge you to go and do the same right now. Nguyen’s philosophy of games has changed the way I think about social media, conspiracy theories and the world in general. The idea that games are fun and addictive because they are simplified and understandable models of the world that you can fit into your brain is fascinating and yet ultimately horrifying when you realise how many of the world’s systems are now based on games mechanics which simplify the world in ways that it should not be simplified.

Many years ago I worked in app development when Serious Games were all the rage. Back then Serious Games meant points and badges. Do a walk? Get a point. Eat your greens? Here’s a badge. The pointsification of everything was frustrating to anyone who had worked in games. People were taking the worst elements of what games were and putting them everywhere. None of the good, clever mechanics were being exploited. For the most part this has only got worse over time. As Nguyen explains, points-based systems are literally everywhere: my watch gives me badges for standing up, walking out for lunch and even remembering to breathe, a little tree grows in our car when it’s driven in an ecologically friendly way and I might get to buy a house if I play the credit score game well enough. There is no doubt that this pointsification is at best annoying and at worst often downright evil but what might happen if the smart, elegant behavioural influencing mechanics from little games like A Fake Artist Goes to New York were applied to the world?

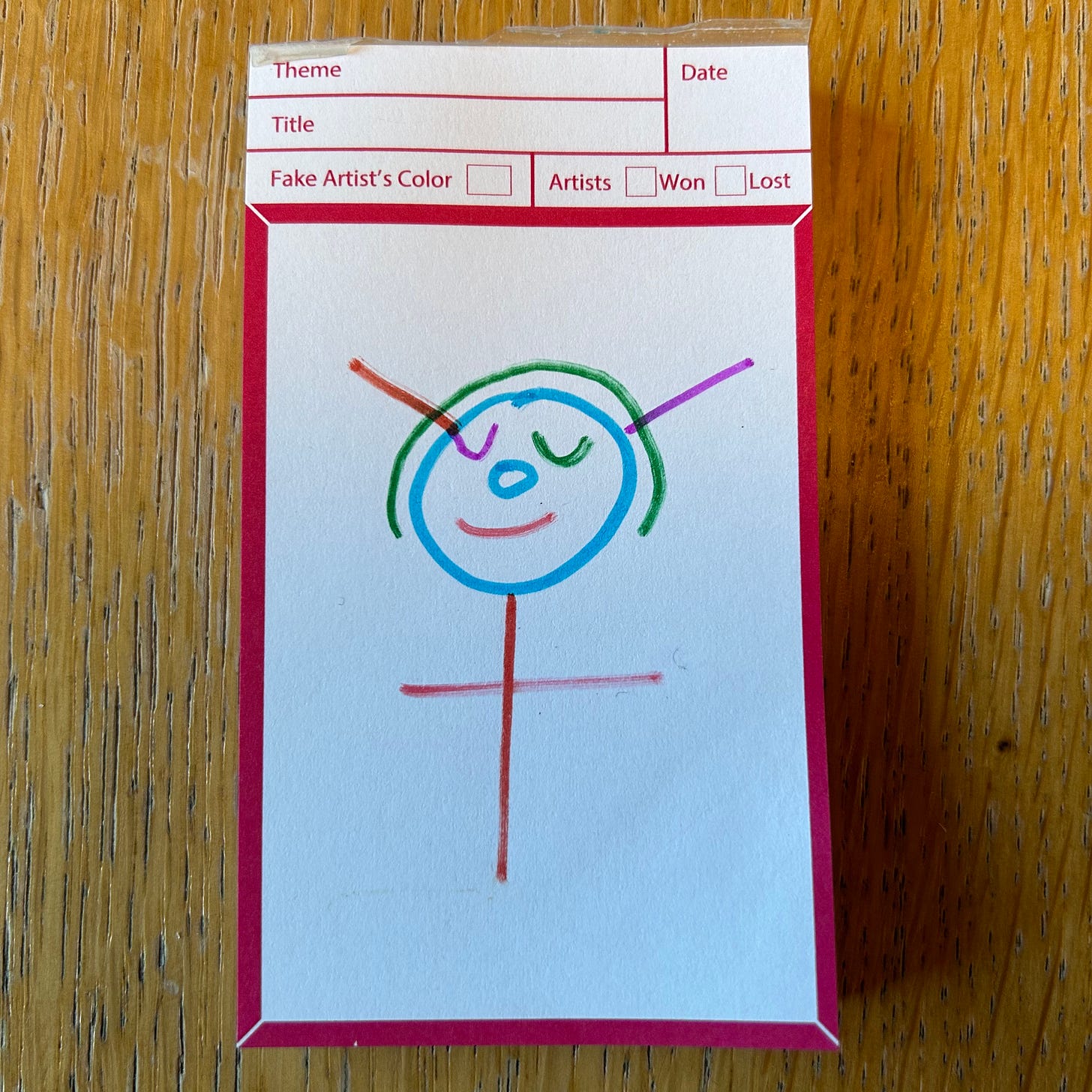

I will leave you with one final tale. One that reveals another really interesting aspect of human nature. The Games Master writes their instruction to the Real Artists on little cards that get passed to the players. The Fake Artist gets an identical card but with an X drawn on it. This Christmas my eldest played the game for the first time. On her first go as Game Master she wrote an X on every card and handed them out. The reveal was astonishing.

You Might Have Missed It…

The New York Times has filed quite the lawsuit against OpenAI for using its copyrighted material to train its AI models. Gary Marcus gives a good overview on his Substack:

The Next Start-Up Unicorn

A business that runs Innovation Workshops. Spend a day with them and end up starting exciting new, groundbreaking projects the very next day.